How is rice grown?

The history of rice

Rice is considered one of the most popular foods in the world. It has fed us for thousands of years and is the main source of nourishment for more than half the world’s population today. Plus, it's delicious.

The domestication of rice is considered one of the most important developments in human history. Beginning in China around 2500 BC, its cultivation initially spread throughout Sri Lanka and India. There are some reports the crop may have been introduced to Greece and the Mediterranean by returning members of Alexander the Great’s expedition to India around 344-324 BC. From China across to ancient Greece, from Persia to Africa, rice migrated across the continents and around the world.

In many cultures, rice is a symbol of life and fertility. It’s a staple food that partners perfectly with red meat, chicken, fish, seafood, tofu and vegetables and easily absorbs the flavour of stocks and sauces.

Where did rice originate?

Rice was first cultivated thousands of years ago in Asia, in a broad arc stretching from eastern India through to Burma (Myanmar), Thailand, Laos, northern Vietnam and southern China.

It's one of the oldest harvested crops known to man. Rice grains discovered at an excavation in South Korea in 2003 are said to be the earliest domesticated rice known. Carbon dating showed the grains to be around 15,000 years old – 3,000 years earlier than the previously accepted date for the origin of rice cultivation in China around 12,000 years ago.

The first written account of rice is found in a record on rice planting authorised by a Chinese emperor in 2800 BC.

Is rice a grain?

Rice is a cereal, related to other cereal grass plants such as wheat, oats and barley.

It completes its entire life cycle within six months, from planting to harvesting. It's also semi-aquatic, which means it can grow partly on land and partly submerged in water. Most cultivated rice comes from either the Oryza sativa, O. glaberrima, or O. rufipogon species.

Rice plants in the Riverina start their life as individual grains sown in irrigated fields that have been landformed to help maximise water productivity. They grow to become green, grassy plants about 60-100 cm tall. Each plant contains many heads full of rice grains that turn golden indicating the plant is ready to harvest.

Rice is generally divided into two types of species: Indica (adapted to tropical climates like South-East Asia) and Japonica (adapted to more temperate climates like in Australia). Indica varieties are usually characterised by having long, slender grains that stay separate and are fluffy once cooked, while Japonica varieties are smaller, round and when cooked are classed as ‘softer’ cooking and are sticky and moist. The Australian rice industry produces mostly Japonica types of rice, although some Indica characteristics have been introduced through a rice-breeding program.

What is in a grain of Rice?

The rice grain is made of three main layers - the hull or husk, the bran and germ, and the inside kernel, or endosperm.

The hull: The rice hull or husk is a hard, protective outer layer that people cannot eat. The hull is removed when the grain is milled.

Rice bran: Underneath the hull is the bran and germ layer, which is a thin layer of skin which adheres it all together. This layer gives brown rice its colour. White rice is just brown rice with the bran and germ layer removed.

Endosperm: The endosperm is the inside of the rice grain, which is hard and white and contains lots of starch.

The rice growing process

Rice planning

Rice farmers grow rice in a rotation with a range of other crops such as wheat, barley and canola, whilst some have also incorporated a mixed farming approach adding livestock and pastures into their farm plans. This farm planning assists them in managing the most efficient use of the natural resources on their farm and ensures they have the most effective rotational system in place.

Most farms use laser-guided land levelling techniques to prepare the ground for production. Laser levelling is one of the most effective and widely adopted techniques to improve water management. Farmers have precise control over the flow of water on and off the paddock.

Rice sowing

Rice seeds are planted from mid-October to early November in the Riverina. Some of the rice grown in the Riverina is planted using aircraft; where experienced agricultural pilots use satellite guidance technology to spread pre germinated seed accurately over already flooded fields.

Over the past 10 years many farmers have moved away from aerial sowing and instead direct drill the rice into dry ground prior to flushing the paddock with water. This change in sowing practice has helped rice growers decrease their water use when growing rice crops

Rice growing

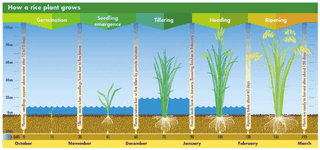

Through November until February, the rice plant grows a main stem and a number of tillers. Each rice plant will produce four or five tillers. Every tiller grows a flowering head or panicle. The panicle forms at the base of the stem called panicle initiation (PI) during which the plant is most susceptible to sterilisation if exposed to cold temperatures at night. Farmers keep their water levels high during this growth stage as the water acts as a buffer and protects the oncoming grain development. As the plant matures into March, the heads of rice fill with grain and turn golden yellow, indicating the crop is ready for harvest.

Over the course of the growing season, water levels on the rice crop vary from 5-25cm of water. This is dependent on the growth stage of the crop. As a rule of thumb, the crop requires a higher level of water as it grows and matures before then decreasing the levels when it matures. Cool night temperatures during PI also warrant deeper water levels to protect the oncoming grain development.

Rice harvesting

As the grain begins to mature, the farmers ‘lock up’ the water on the bays. This means no water leaves the paddock, it is fully utilised by the rice plant. Once the rice plants are ready for harvest the farmers begin to drain their paddocks into their water recycle drains ready to be used for another crop. Once the soil has dried out enough, the rice is ready to be harvested.

Farmers use large, conventional grain harvesters to mechanically harvest rice in Autumn.

Once harvested, the rice is commonly named paddy rice. This is the name given to unmilled rice with its protective husk in place.

Storing rice

Once harvested, a truck transports it to one of the industry’s paddy storage facilities, where segregation occurs according to variety. Rice storage bins are fitted with computer-linked sensors that monitor grain storage conditions and keep the rice at a suitable temperature and moisture level.

Rice processing

Rice mill

Australian rice mills use some of the most advanced equipment and are extremely efficient.

When the storage manager receives orders and shipping instructions, the rice is trucked from one of 16 rice storage and drying facilities to one of two industry mills located in the north and south of the Riverina. The industry also has three stockfeed manufacturing plants.

Milling rice steps

Step one – Removal of hard protective husk.

The rice husk is the protective layer surrounding the grain. Once removed, the rice grain is packaged as brown rice. Because it still contains the rice germ and outer bran layers, brown rice contains more fibre and vitamins than white rice.

Step two – Removal of the germ and brown layers

Gentle milling removes the germ and bran layers from the grain to expose a white starch centre. The polished white starch centre is what we know as white rice.

Rice by-products

By–products from the growing and processing of rice create many valuable new products. Rice husks, rice stubble, rice bran, broken rice and rice straw are used as common ingredients in horticultural, livestock, industrial, household, building and food products.

Rice husks

The rice husk is the hard, protective shell on the grain. The removal of the rice husk is the first stage of rice milling. Rice husks are the main by-product of rice production. For every one million tonnes of paddy rice harvested, about 200 000 tonnes of rice husk is produced. Rice husks are used in 2 main ways.

- raw - animal bedding, growing seedlings, improving mulch for gardens.

- ground and processed – is used in stock feed, potting mixes and pet litter.

Rice stubble

Rice stubble is the stalks and roots of the rice plant left in the ground after it has been harvested.

Rice stubble is very thick and difficult to deal with. Livestock graze on recently harvested paddocks and eat some of the rice stubble. A portion of the remaining stubble is usually burnt off and a winter cereal crop, such as wheat, is planted. On some rice farms, rice stubble is left to break down naturally and is incorporated into the soil, to improve the soil structure. Some stubble is baled and removed from the paddock as rice straw. The majority of this is used as stockfeed to supplement diets in mostly beef and dairy cattle. Additionally, due to its slow rate of breakdown and weed free nature, it makes excellent garden mulch.

Rice bran

Rice bran is the outer layer of the brown rice grain. The rice bran is removed during the milling process if white rice is to be produced.

Stabilised rice bran is sold as a health food in supermarkets and health food shops, or to food manufacturers who use it as an ingredient in foods such as crispbreads and breakfast cereals.

Unstabilised rice bran can be used in stockfeed and for other animal and industrial products.

Broken rice grains

During the rice milling process some of the rice grains break. Most of these broken grains are removed from the milling process. The larger broken rice grains are used in pet foods and stock feed, or breakfast cereals. The smaller broken rice grains are ground into rice flour which can be used in baby foods, snack foods, including rice crackers, muesli bars, or as a baking ingredient. Ground broken rice grains are also used in manufactured foods, such as sausages and milk powder drinks.